How Oregon’s New Anti-Poaching Law Protects Sensitive Wildlife Location Data

Wildlife poaching is a global phenomenon, but many people don’t realize that it’s also a growing concern in the U.S. Oregon is no exception. Illegal take of individuals of wildlife species, especially those that have game value or black-market value, is only growing.

Defenders of Wildlife has been actively engaged in addressing the threat of poaching in Oregon and when we learned during winter of 2018 that extremely sensitive wildlife location data (including radio collar data and frequency, and exact location of sensitive habitats such as nesting and denning site used for research and monitoring) was available to the public, we recognized the potential threat to vulnerable individuals and decided to take action immediately. Because of our work with a diverse array of partners, we were able to balance the need for public access to information with protecting highly vulnerable species in an Oregon state bill. With hard work and dedication, we got the bill passed within six months and in its very first round of introduction to the legislature during the 2019 Oregon legislative session! Governor Brown signed the bill on July 16th, making it an enforceable policy to protect wildlife in Oregon.

This process was not an easy one. To start with the problem, one six-year study in Central Oregon found that poaching was responsible for 20% of the region’s mule deaths, which was more than the number of licensed hunts in the region. Additionally, 80% of those illegal kills were females which represents a real threat to the future of the population. In another instance in 2018 during hunting season, troopers working in the greater Yamhill and Washington county areas seized 27 firearms used in illegal activity, 16 of which were used to shoot Wildlife Enforcement Decoy animals at night. Poaching data in Oregon from 2015 for deer and elk indicate nearly 500 deer and more than 200 elk were killed illegally. These two species also happen to be the species with highest number of monitored individuals by Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW), which is why we have better data on the impacts of poaching. For most other species we lack such crucial information but if elk and deer poaching can be considered as indicator species in this instance, then we have a grave situation in Oregon when it comes to protecting our wildlife species and their most vulnerable individuals.

One of the main concerns for Defenders was the public accessibility of sensitive wildlife location data. ODFW maintains data pertaining to the exact location of individuals that have been radio-collared by the agency or monitored on other ways, as well as the location of sensitive habitat use such as breeding grounds, nesting or denning sites and spawning grounds. Such data is essential for the agency to make critical decisions related to the recovery and management of Oregon’s wildlife; however, it also puts these individuals and their population at risk of being harmed or harassed. Until the summer of 2019, any member of the public could access such sensitive wildlife location data, including radio collar frequency, real time location and location of active dens, breeding or nesting sites. In case of species that reuse their breeding or nesting sites throughout their life such as wolves, it compromised their safety year after year and in case of species that tend to stay in groups or aggregate during certain life stages such as sage grouse, identifying the location of one individual could compromise tens or hundreds of other individuals.

Wildlife research and monitoring require a large investment of taxpayer dollars by ODFW. Therefore, failure to protect such data might not only mean failure of a long term and expensive research project or setting inaccurate management goals but also loss of expensive equipment such as radio collars. Losing money that the state is committing to wildlife conservation is a waste of taxpayer dollars – taxpayers who care about the environment and wildlife. Investment is wildlife conservation from federal or state governments are always limited, so minimizing such waste of precious tax dollars was especially to us.

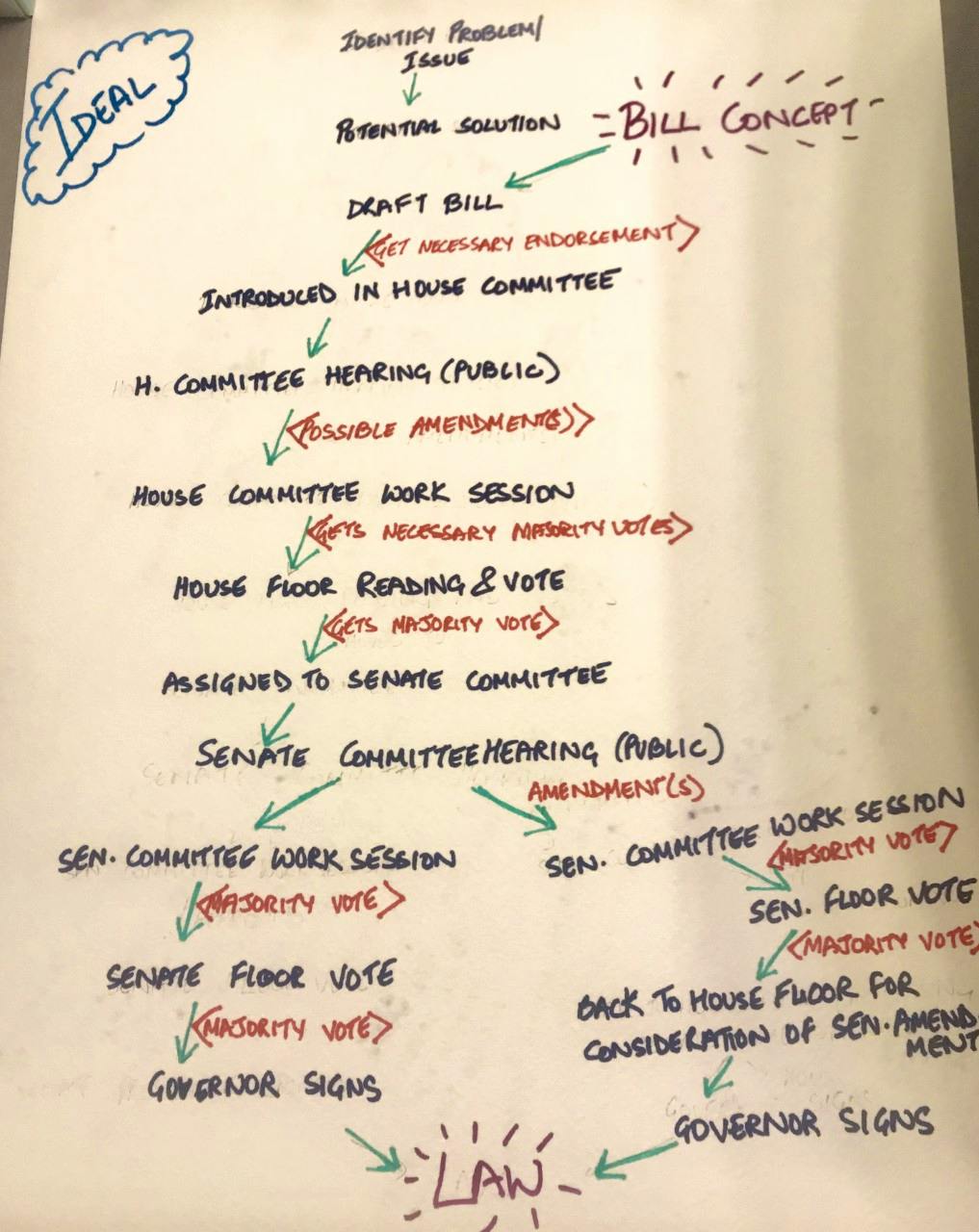

In response to this glaring gap in Oregon’s wildlife policy, Defenders of Wildlife put forward a bill during Oregon’s long legislative session that started in January of 2019. The bill, HB 2841, was drafted to protect such sensitive wildlife location data by removing open and unrestricted public access to such information. HB 2841 introduced a discrete measure that would help address some of the concerns around illegal hunting and poaching in Oregon. While we recognize that such access to such information is sometimes needed by members of the public to make right management decisions about their land and land-use practices, we could also see the potential threat it poses to the monitored wildlife individuals from those that intend harm. For most land use decisions, data aggregated to a scale higher than real time location could suffice the need of a landowner. Our goal, therefore, was to find a balance between public access to information and protecting highly vulnerable species. We achieved that by outlining the circumstance and species for which such information can be withheld and at the same time providing exemptions under circumstances that would have direct implications on research and education, wildlife management and to make land use and livelihood decisions.

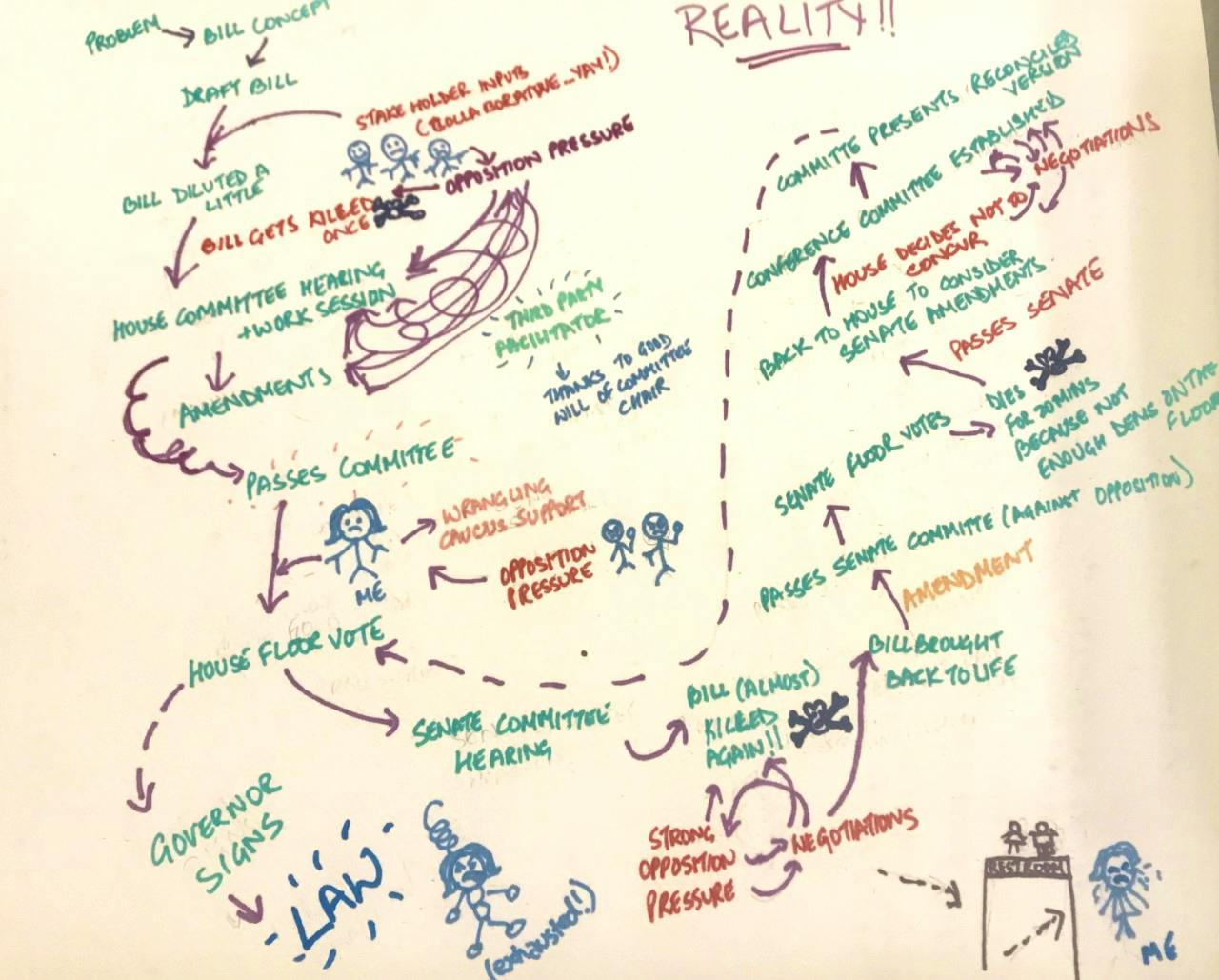

HB 2841 was introduced through the House of Representatives, with Rep Gomberg as the Chief Sponsor and Rep Witt, Rep Lively, Rep Brock-Smith, Rep Gorsek, and Rep Helm as the Co-Chief Sponsors. The bill had a tough and long journey through the House of Representatives and the Oregon Senate. It faced severe opposition from lobbyists that represented the interest of groups who wanted to maintain access to such information. In order to address some of those valid concerns, the bill went through amendments to accommodate the needs of groups and individuals that need such information to make critical decisions around livelihood and land use management. We recognize that working with all of these stakeholders is an important part of both the legislative process and living with wildlife. HB 2841 struck a delicate balance of protecting the information from those that have malicious intent or mean harm, while maintaining access for those that truly need it for wildlife management, research and education or protecting their livelihood.

Despite the amendments, the bill continued to face strong opposition from powerful lobby groups, but Defenders worked actively to educate legislators and advocate for this critical wildlife policy in Oregon. With the support of a few legislative champions who took a stand for wildlife, Defenders succeeded in getting HB 2841 passed through Oregon’s turbulent 2019 session. It is a big victory for wildlife in Oregon, and an added layer of protection for especially vulnerable individuals of wildlife species. By passing this law, Oregon has committed to addressing concerns around poaching in the state and Defenders will continue to work with public agencies and decision makers such as state legislators to ensure that conservation actions on the ground are backed by strong wildlife conservation policies.

Follow Defenders of Wildlife

facebook bluesky twitter instagram youtube tiktok threads linkedin