When you hear the term “sky island” what do you imagine? Maybe something from a far-off fantasy land, or an alien planet? Well, what if I told you that sky islands aren’t just real, they are scattered along Southern Appalachia and house species who have called this land home for millions of years? Now, you may be thinking, “I have never seen a floating island while visiting the mountains in Southern Appalachia.” That’s because the term sky island doesn’t refer to landscapes resembling the world Pandora of the movie Avatar but rather refers to remnants of the Pleistocene Epoch that remain only in the high elevations of our eastern mountain range.

The Pleistocene Epoch lasted from 2.6 million years ago until 11,700 years ago. During this time, glaciers covered much of North America making the southeastern United States a boreal forest comprised of spruce/fir and northern hardwood species. As the Pleistocene Epoch ended and the climate began to warm, the glaciers and boreal forests retreated northward. But Canada wasn’t the only place to escape the heat; the Southern Appalachia mountains’ highest elevations also provided a safe harbor for boreal forests. Now, these Pleistocene relics sit only on the top the tallest mountains in Southern Appalachia - creating sky islands that host many species marooned as the ecosystems they need to survive vanished.

Our Workshop & Walkabout this summer was focused on one of these marooned species, the federally endangered Carolina northern flying squirrel. The Carolina northern flying squirrel is a distinct subspecies of the northern flying squirrel due to the isolated nature of these mountain-top populations. At our workshop, Sue Cameron, a biologist with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, spoke to us about this unique species and why it needs sky islands to stay alive.

The primary food source of the Carolina northern flying squirrel is the truffle, which is the fruiting body of fungal mycorrhizae. Fungal mycorrhizae attach to the roots of spruce/fir trees and aid in gathering water and nutrients for the tree while the fungus receives sugars from the roots. The squirrel in turn helps keep spruce/fir forests healthy by digesting and disbursing the truffle spores the trees need to thrive. Due to this fascinating symbiosis, the primary food source of the squirrel is thus restricted to patches of boreal spruce/fir forest. The squirrel requires not just the spruce/fir, but also northern hardwood species, specifically the yellow birch. The shaggy birch bark is easy to strip off the tree and makes warm nest insulation.

Unfortunately, we also discussed how the sky islands are threatened and vanishing. Initially, natural warming after the Pleistocene Epoch caused a decline in habitat, but in the late 1800s/early 1900s extensive logging and slash burning caused a drastic drop in Carolina northern flying squirrel habitat. Our region’s soils were decimated by the slash fires and spruce seedlings could not re-establish. This led to as much as 50% of all Southern Appalachia spruce/fir forests being replaced by hardwood species that support the hard mast diets of the common southern flying squirrel, but not the truffle and lichen diet of the endangered Carolina northern flying squirrel. Introduced pests, like the balsam woolly adelgid, and acid rain also have been accelerating the decline of spruce/fir forests and habitat retractions are also predicted as a result of climate change.

Thankfully, good news arrived as Anna Norton of Southern Highlands Reserve joined the presentation live from the Reserve via video chat. The Southern Highlands Reserve is part of a partnership called the Southern Appalachian Spruce Restoration Initiative (SASRI) whose goal is to increase the size, variability and connectivity of remaining spruce patches. This process begins with partners collecting spruce cones from the wild growing them into saplings at the Southern Highlands Reserve before planting them back into the wild. The first true restoration project of this partnership occurred in September of 2017 in the Great Balsams. Forest restoration like this will not only help the Carolina northern flying squirrel but other listed species who call the spruce/fir forests home such as the spruce-fir moss spider, northern saw-whet owl, and pygmy salamander.

Carolina northern flying squirrel monitoring is needed to locate areas of priority for spruce restoration. One trusted tactic is to hang nest boxes within squirrel habitat for denning. The wire mesh nest bottoms allow for draining and easy monitoring. All a field-worker needs to do is look up the tree at the bottom of the box to determine if it is empty or holding a nest. To assist the cause, our workshop ended with us building 12 new nest boxes that were donated to the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission for use in monitoring. These boxes will help the recovery effort and assist in locating new areas for forest restoration and Carolina northern flying squirrel survival.

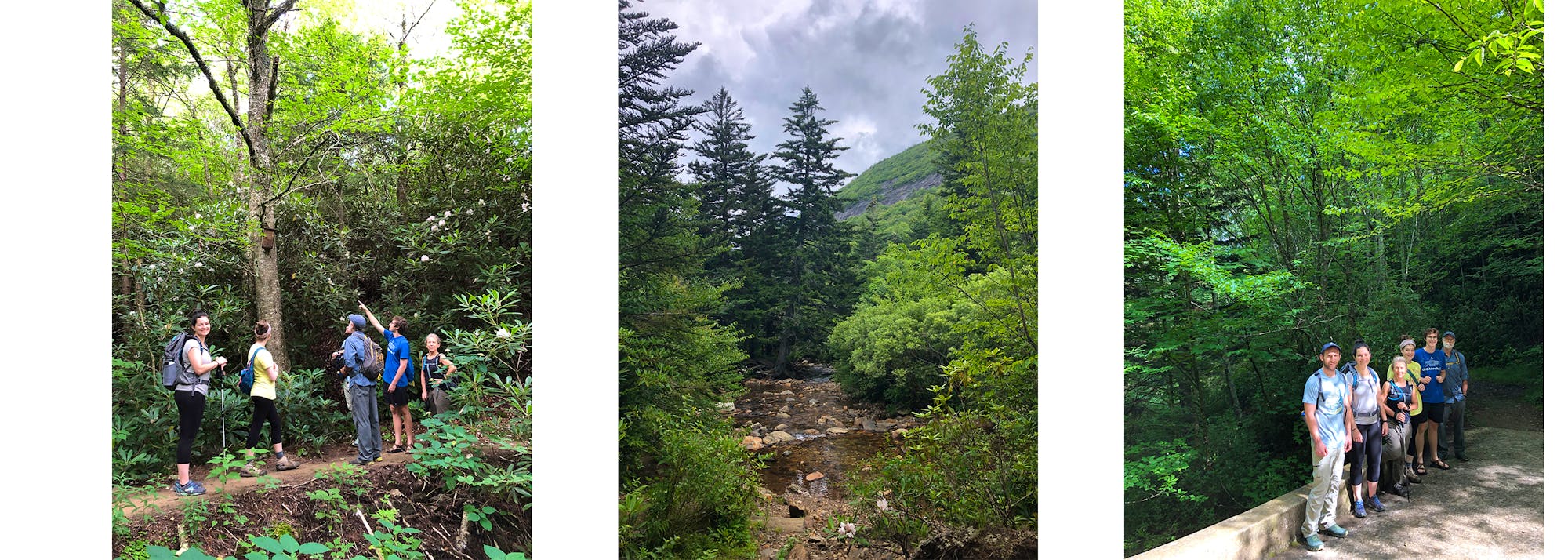

Our walkabout portion the following Saturday was a hike through prime Carolina northern flying squirrel habitat in Pisgah National Forest, Pisgah Ranger District. We hiked along the Flat Laurel Creek Trail -- a hotspot for the squirrels and the location of several large-scale spruce plantings by SASRI. On our hike, we enjoyed the beauty of this high elevation forest and located multiple nest boxes, many of which had nests demonstrating the number of squirrels present and the success of the restoration process.

While attending this Workshop & Walkabout I was amazed to learn about a creature who has lived in Southern Appalachia for millions of years yet faces extinction –a relic of a time that is almost forgotten. These creatures and the unique sky islands they inhabit are just one more part of the intricate and beautiful puzzle that is Southern Appalachia. I am very grateful to Weiler Woods for Wildlife for graciously sponsoring our 2019 Wildlife Workshop & Walkabout series and making this experience possible so that Defenders can share a love and concern for wildlife and wild places with those living in the area. We would also like to thank Deltec Homes who kindly donated the wood needed for the nest box construction.

I highly encourage anyone interested in learning about the natural world that surrounds us to attend the upcoming program -- Monarch Butterfly Migration. In addition to learning about this imperiled creature, you’ll get to make native wildflower seed bombs to drop for easy habitat creation. For more information please contact Tracy at southeastoffice@defenders.org and join the Carolinas Facebook group to stay up-to-date on these events and more!

-Logan

From the Blog

Follow Defenders of Wildlife

facebook bluesky twitter instagram youtube tiktok threads linkedin