Species Lost

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) periodically updates its workplans for future species listing decisions under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), and the latest plans are a doozy. The agency is preparing to delist 23 species under the act because they are extinct.

Gone.

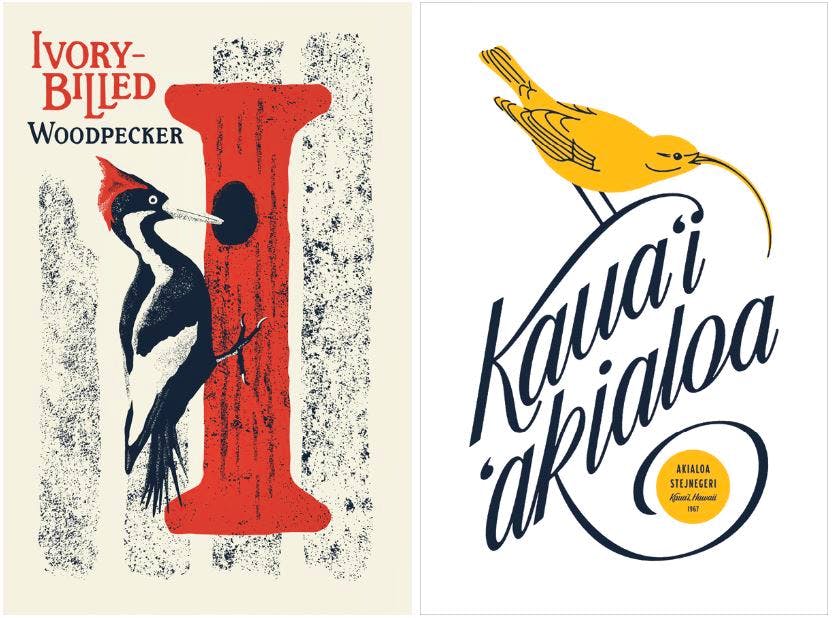

Some of these are species that we hoped beyond hope might still occur in the wild, like the emblematic ivory-billed woodpecker. Some are Hawai`ian birds, a guild that is suffering from seemingly insurmountable threats. Some are freshwater mussels — indicator species for water quality and healthy watersheds important for wildlife and people.

All but one of these species occurred in U.S. states or territories; they were not far off, foreign critters or plants. They might have been seen in your backyard in Georgia or favorite stream in Tennessee or during a special birding trip to Hawai’i.

It’s a big deal when the federal government officially declares a species is extinct, let alone 23. And it’s especially chilling given the recently reported global biodiversity crisis.

The news of these extinct species further underscores the pressing need to invest in conservation and defend and strengthen the ESA and other conservation laws that are essential to wildlife conservation and recovery. We need new, innovative and collaborative strategies for more effective, efficient conservation planning and management. And we need to protect forests, grasslands, deserts, wetlands, riparian and marine habitats across all land ownerships — on federal public lands, like the National Park System and National Wildlife Refuge System, as well as tribal lands, state lands and private lands nationwide.

Species Saved

FWS’s workplans also offer reason for hope. The agency is proposing to delist species that are successfully recovered due to the protections of the ESA. This visionary law came too late for the ivory-billed woodpecker, which had declined to just 20 individuals in the wild decades before the ESA was enacted. But the Kirtland’s warbler and Foskett speckled dace benefitted from the ESA’s protections and robust recovery plans and are now scheduled to come off the federal threatened and endangered species list.

The Kirtland’s warbler was one of the original species listed under the ESA when it was passed in 1973. Its scant population, reduced to an estimated 200 breeding pairs, has increased to nearly 2,400 thanks to federal protections, conservation investment and education, and collaborative conservation efforts within its summer range in Michigan and Wisconsin.

The Foskett speckled dace, a small fish known only from a pair of springs in Oregon and listed due to a variety of localized threats, is another success story. Listing required the Bureau of Land Management to fence off the springs to protect against habitat degradation by cattle and for authorities to protect the aquifer from water withdrawals. Together with Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, federal agencies are now managing the species’ habitat to preserve the species into the future.

Fighting for Imperiled Species

Between the extinctions and the ESA successes, however, the FWS workplans contain a series of deeply troubling proposals. The FWS is arbitrarily rushing some species across the goal line of “recovery” while ignoring the best available science showing they are still decades away from potential removal from the threatened and endangered species list.

These species still need the ESA. Population trends, habitat loss and other factors continue to imperil a number of animals targeted for downlisting or delisting, including the Canada lynx, Key deer, red-cockaded woodpecker, and the Southeastern beach mouse. The Species Status Assessment for lynx released in 2017 demonstrated a severe decline in the lynx population by the century’s end. Each year, we lose 5–15 percent of the Key deer population to motor vehicle collisions and each hurricane brings more worry for the Florida islands they inhabit. Southeastern beach mice will face even more dire living conditions as development, sea level rise, erosion and stronger storms impact the habitats they rely on.

Without federal protections and proactive conservation strategies, declaring “recovery” is no different than throwing in the towel on these species. ESA protections must be given time to work to produce consistent measurable conservation and recovery for listed species.

Sadly, the FWS is also making unsound decisions and using mental gymnastics to justify not listing species in need of federal protection. The Eastern hellbender is expected to continue to rapidly decline across its range and the agency proposes doing nothing except listing the one isolated population that is functionally extinct.

For more than 40 years, the ESA has helped prevent the extinction of our nation’s treasured fish and wildlife, including American icons like the American alligator and the California condor. I had the honor of removing the peregrine falcon from the list of endangered species as the Director of the Fish and Wildlife Service in 1999. The Act’s success stories are proof that it works if we commit to implement the law as Congress intended.

Defenders of Wildlife is singularly committed to conserving imperiled species and the habitat they require. We grieve the loss of extinct species, our fellow passengers on planet earth. We celebrate when species are recovered from the brink of extinction. And we will call out FWS when it is rushing to declare imperiled species as recovered and failing to provide species the protection they need.

- Jamie

Follow Defenders of Wildlife

facebook bluesky twitter instagram youtube tiktok threads linkedin