A border wall would devastate wildlife in the U.S. and Mexico. Defenders’ ground-breaking new report In the Shadow of the Wall explains how the wall would affect five critical conservation hotspots — areas with great biodiversity and immense investment in protected lands. These are the last refuges for many imperiled border species already under assault from overgrazing, exotic species, roads, mining, water withdrawal and other human activities.

These hotspots straddle the border, each extending roughly 100 miles into the U.S. and Mexico.

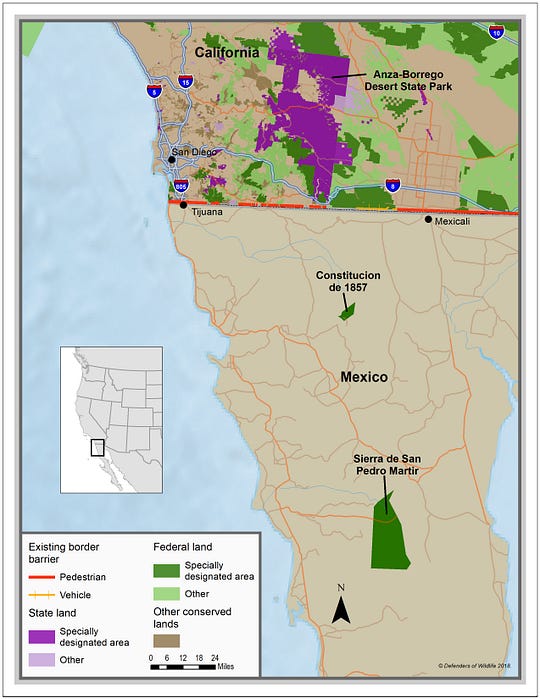

The Californias

The coast of southern California and northern Baja California sustains over 400 species of plants and animals classified as at risk, threatened or endangered. A Mediterranean climate with wet, mild winters and hot, dry summers creates this biodiversity hotspot with unique seaside vegetation, grasslands, deserts, vernal pools and scrub. Endangered fauna, like the San Diego fairy shrimp, Peninsular bighorn sheep, Quino checkerspot butterfly and the famous California condor call this biologically important region home.

More than 1,300 square miles of federal and state protected lands exist on both sides of the border, primarily in California, where there are many protected wildlife refuges, state parks, ecological reserves and wilderness areas. On the Mexican side there are two major federal areas — the San Pedro Mártir and Constitución de 1857 national parks. These two protect mountains, home to golden eagles, mountain lions, bobcats, ringtails, mule deer and endangered Peninsular bighorn sheep.

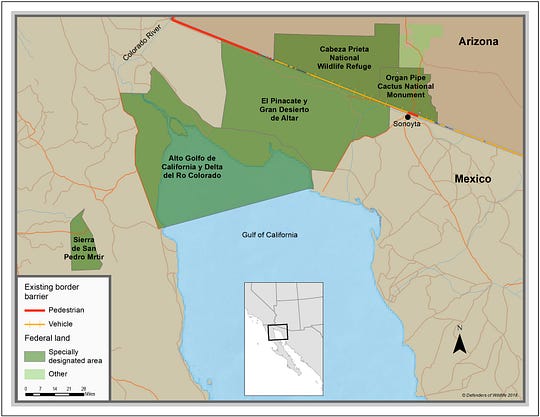

Sonoran Desert

The Colorado, Santa Cruz and San Pedro rivers bring water and support abundant life in the Sonoran Desert. There are more endemic plant species here than anywhere else in North America, and a multitude of animals adapted to living in its harsh and extreme climate include 60 mammals, 350 birds, 20 amphibians, 100 reptiles and 30 fish.

Although beset with booming development around Phoenix and Tucson, the Sonoran Desert still has vast stretches of remote, largely intact wild lands. The border is sandwiched by huge reserves on both sides — in Mexico two biosphere reserves, El Pinacate and Alto Golfo de California, protect almost 9,000 square miles. On the United States side thousands more acres are protected by Saguaro National Park, national monuments and national wildlife refuges, along with multi-use areas, easement areas and protected county lands. These are home to imperiled cactus ferruginous pygmy owls, desert bighorn sheep, Sonoran pronghorn antelope, southwest willow flycatcher and Gila chub.

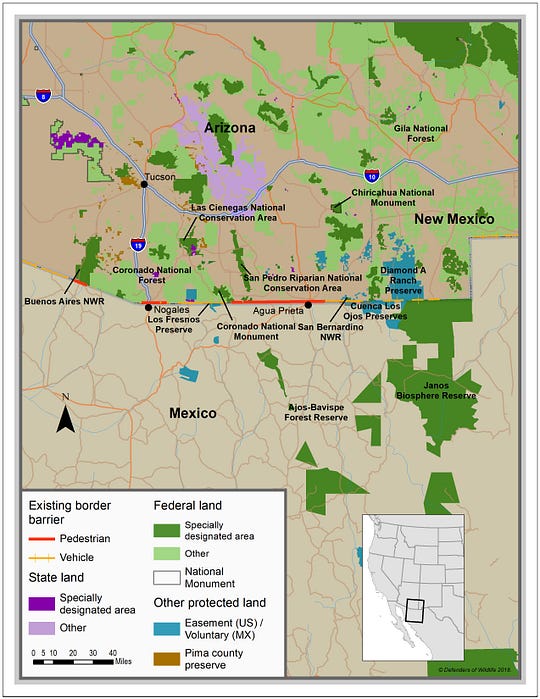

Sky Islands

This region is named after its signature sky islands — forested mountain ranges rising from a sea of desert flatlands. It is one of the most biologically diverse places in the world, where temperate and subtropical zones come together. The ranges of jaguars overlap with black bears, military macaws with bald eagles. A ribbon of green winding through the arid land, the San Pedro River is the last undammed river and one of the most important migratory flyways in the Southwest for 300 species of birds, 200 species of butterflies and 20 species of bats as they fly from Central and South America and back.

Recognizing the biological importance of the Sky Islands, a variety of property owners in the United States and Mexico, including agencies, nonprofit groups and individuals have made monumental investments in conservation lands. A complex of United States and Mexican protected areas straddle the border for over 60 miles, including private ranches, San Bernadino National Wildlife Refuge, San Pedro Riparian and Las Cienegas National Conservation Areas, over 1,000 square miles of wilderness and Janos Biosphere Reserve.

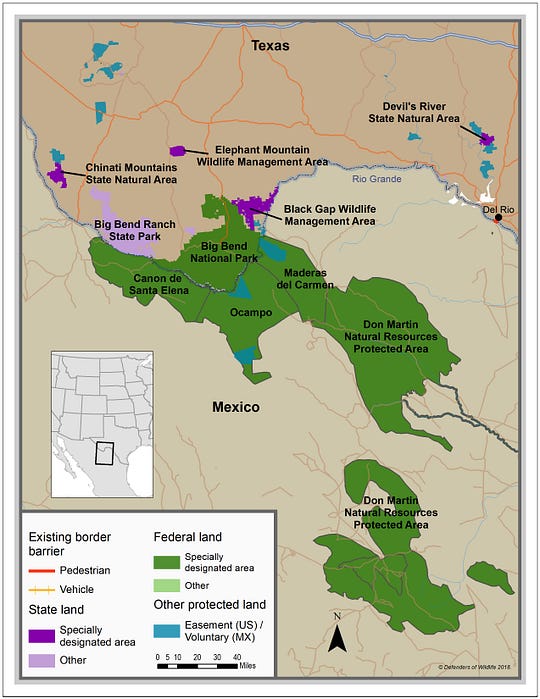

Big Bend

As the Rio Grande River passes through the Chihuahuan Desert, it changes direction, swinging up to the northeast and giving the region its name: Big Bend. The Chihuahuan Desert is home to 446 species of birds, 3,600 species of insects, 75 species of mammals and more than 1,500 species of plants.

Even though much of the desert is remote from population centers, the landscape has been changed by human activity: damming rivers, withdrawing water, overgrazing, introducing exotic plants and lethally controlling the populations of predators have all had a hand in altering Big Bend. The silvery minnow and other native fishes are imperiled, the western yellow-billed cuckoo and southwestern willow flycatcher are on the endangered species list. Jaguars, once common, no longer exist in Texas.

The 4,687-square miles of protected areas in the Big Bend region of the United States include Big Bend National Park, flanked by Big Bend State Park and the Black Gap Texas Wildlife Management Area. Across the river in Mexico are several reserves managed by the Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas. Because of their global ecological importance, Big Bend National Park and one of the Mexican reserves, Maderas del Carmen have been designated International Man and the Biosphere Reserves by the United Nations.

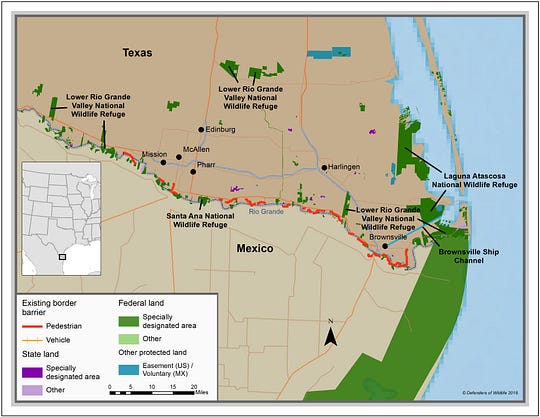

Lower Rio Grande

Although the Lower Rio Grande Valley has been transformed by agriculture and other development, the federal government has been buying land since the 1940s in a desperate race to preserve it before it’s developed. Most native thorn, riparian and delta forests are now gone, but the government’s purchases have protected the largest remaining piece of delta forest in the tiny Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge, only three-square miles. Two other national wildlife refuges, Lower Rio Grande and Laguna Atascosa, are the extent of the federally protected lands, and together they are home to banded armadillos, Texas tortoises, Mexican free-tailed bats, 300 species of butterflies and 400 bird species, including the endangered Alpomado falcon. Once home to a large population of ocelots, the Lower Rio Grande now has fewer than 100, though conservationists hope to one day join these U.S. ocelots with the larger population in Mexico. South of the U.S. refuges, the massive 2,212-square-mile Laguna Madre y Delta Del Río Bravo Biosphere Reserve extends for 220 miles along the coast.

The above five biological hotspots protect some of the best, last remnants of our natural heritage. But these hotspots are under threat from many anthropogenic factors. Adding a new threat — a border wall — will make conservation of many rare species more difficult or even impossible. If completed, the wall will be an insurmountable barrier to genetic diversity and healthy populations of species like the endangered Sonoran pronghorn and Mexican gray wolves; it will prevent endangered bighorn sheep in the U.S. from reaching calving grounds and water sources in Mexico; and it will stop adventurous jaguars from travelling up from Mexico to settle in the Sky Islands of Arizona and New Mexico. A wall will put at risk decades of binational collaboration, in which, conservationists and citizens have built friendships and working relationships as they try together to protect and restore our shared natural heritage.

Follow Defenders of Wildlife

facebook bluesky twitter instagram youtube tiktok threads linkedin